NEWSLETTER

BE FIRST IN LINE FOR OUR NEXT RELEASE.

© 2025 TIPSTER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

NEWSLETTER

BE FIRST IN LINE FOR OUR NEXT RELEASE.

Words by Marcelo Jaimes Lukes

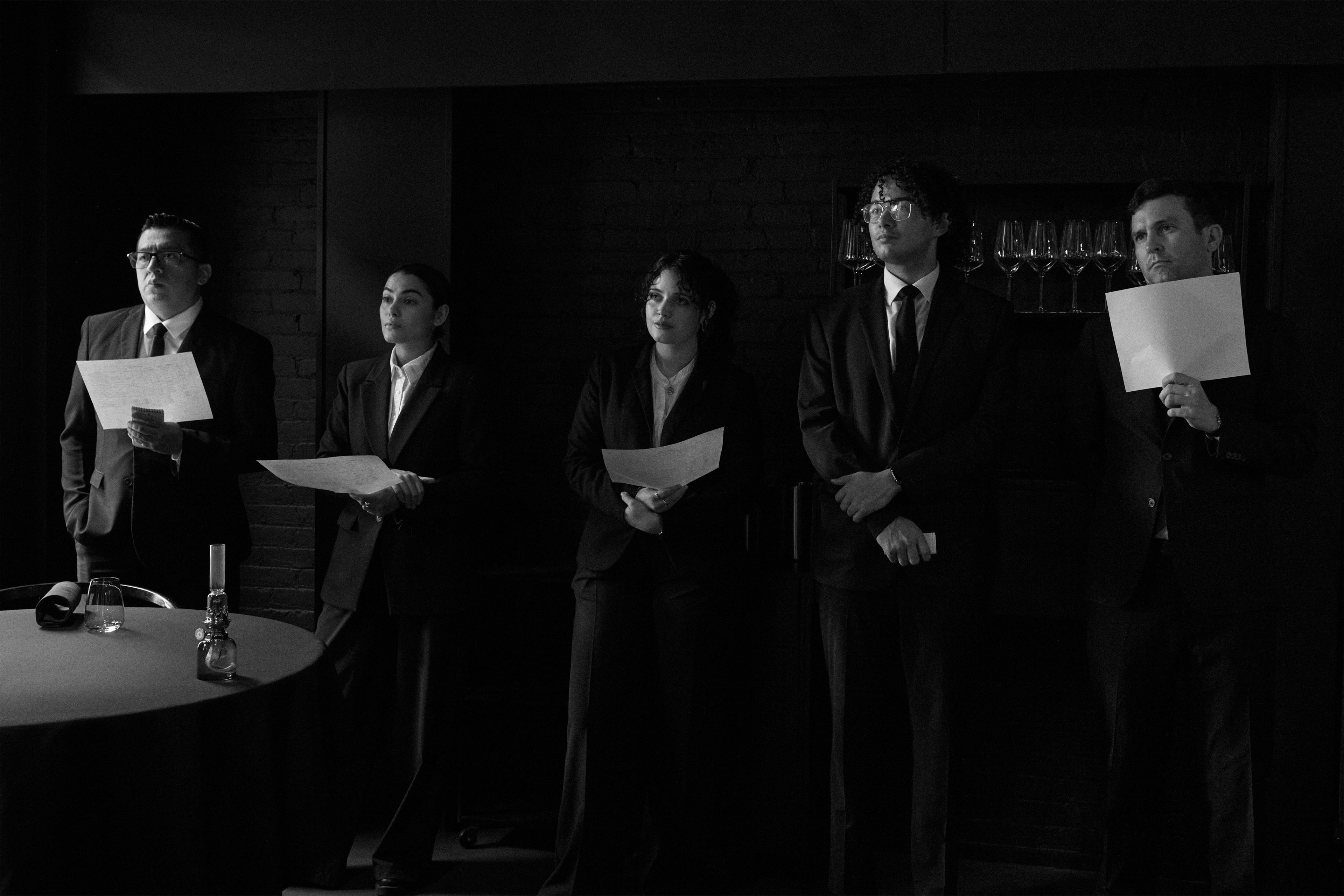

Photography by Sacha Maric

For Fredrik Berselius, cooking is less about flavors than feelings: the silence of the Nordic taiga, the scent of mushrooms after rain, the chaos of the Atlantic coast. At Aska, his two-Michelin-star restaurant in Williamsburg, his memories in the wilderness take form on the plate. They’re preserved, foraged, and timed to reflect the fleeting seasons of the Northeast.

MARCELO JAIMES LUKES: You were raised quite far away from Brooklyn’s culinary scene. What role did food play in your life growing up in Stockholm?

FREDRIK BERSELIUS: Making food was an important part of my upbringing, but I was mostly intrigued by nature. There was a lot of running around in the woods. I suppose that’s because there’s a mystical aspect of being in a Scandinavian pine forest. We went mushroom hunting and foraging for blueberries and lingonberries. Spending time close to nature was about seeing what was growing in the wilderness, learning from your surroundings, and then finally, what you could eat from it. We didn’t do this in an obsessive way (laughs), these were just things we did like, like many Scandinavian families.

MJL: How are these memories of the wilderness reflected in the dishes you create at Aska?

FB: When you both cook and eat, you start piecing this map of your memories together, little by little. You are connecting the dots of everything that has come before. You realize you’ve had these moments in your life that have affected you. That’s what I try to do with my cooking now. I draw from moments in my life that I want to bring back to the guests that dine with us: fishing for herring, making fruit preserves, baking bread, and foraging for mushrooms in the pine forests.

MJL: New York City isn’t known for its pine forests. What brought you to Brooklyn?

FB: I always knew I wanted to be in New York. Early on, I was dabbling in arts, engineering, and design, and I found the restaurant world here to be the intersection of so many creative things. That’s what fascinated me about being here: the creativity combined with the rush and the adrenaline and the push. Both New York and its kitchens have an endurance aspect to them.

When I started cooking here, Noma and Scandinavia in general were at the very forefront of this new Nordic movement in restaurants. That was another indicator that what I wanted to do was “on the right track,” so to speak. Living in New York and being from Sweden, I wanted to make food that told the story of where I’m from.

MJL: Did you intend to change people’s perception of Scandinavian cuisine?

FB: I suppose so. At the time, Scandinavian food and Swedish food in particular were just associated with meatballs and herring. That’s not what I wanted to do. I was inspired by avant-garde chefs who were pushing the envelope. At the same time, I wanted to share the story of where we are—New York. I wanted to tie it all together.

What made me stay here was finding these similarities in Upstate New York and the coastal region up to Maine. That brings me back to Scandinavia and allows me to cook in a way that represents both this region and where I come from.

I still go back to Sweden and Scandinavia regularly—I find it inspiring and refreshing. I love going back to a Nordic sea or a Nordic forest.

MJL: I’m curious about that connection you’re drawing between the Northeast and Scandinavia—what specifically do you find similar, the wildlife, the forests?

FB: It’s more of a feeling. I’m inspired by the feeling of being in a place. I don’t draw on specific dishes, not even flavors. I’m inspired by the feeling of being in a damp, mushroom-scented forest, the feeling of being on the rugged coastline, the feeling of standing in a flowering meadow in the summertime. I want to transport guests from the dining room to those places. I want to bring those feelings back to the dishes that we serve. That’s a tricky thing.

We use a lot of ingredients we’ve collected ourselves, or grown ourselves, and preserved through the year, together with the best purveyors we can find. In the kitchen, you have to put on your filters. You have to squint your eyes. You have to really dream.

Nature in general is magical. It is a place to reset and reenergize yourself. It’s a place to get away from Brooklyn and come back with a clean mindset.

MJL: How do you and your team communicate the stories behind the food that they might be unfamiliar with—things that are foraged, preserved, and harvested?

FB: There is definitely a conversation that takes place between our kitchen team and the guests who are dining. It’s a balance. We don’t want to make this a boring class on biology. We want to share the exciting and delicious things that are out there, whether they are flowering trees that you walk past every day on your block or something that grows a couple of hours from here.

We’re also learning that we have to meet people where they’re at. When someone comes in, I don’t know what they're familiar with or what kind of food they eat. We want to make this a fun and enjoyable experience, not a lesson. It’s a conversation. It’s up to the guest to engage as much as they want.

Here’s the thing: the food alone should be good enough by itself. Of course, it has a story, but it shouldn’t need any explanation.

But if you’re more familiar with something, then you can look closer at the elements and the details. To me, it’s like anything beautiful: wine, music, dance, art, design. If you engage with it, you find even deeper levels and nuances.

MJL: You mentioned your own experience with design and architecture. Aska is quite a stark environment, notable for its black walls and moody lighting. How did you decide on this poetic environment?

FB: The funny thing is, we were strongly recommended against making the restaurant black. The people working on it actually refused to paint it black. But the design has to do with the name: Aska means ashes in Swedish. We wanted to create an understated environment where there weren’t distractions—your own table, your own lighting, where the dining room fades out like a fog.

The focal point is always the food, the wine, and the service. To that end, a design that appears simple can often be the most difficult to execute. I like clean lines. I like the understated. I wanted to showcase the few elements of the space that were from old New York: massive wood columns from the 1850s, parts of the space that were left behind from when it was a textile factory.

We have a garden adjacent to the dining room, which is a little green oasis that acts as a window into the seasons. If it’s summer, the flowers and herbs that you see in the garden will also be on your plate. If it’s winter, you see that nothing is growing outside, and the menu reflects a starker style.

But in terms of design, this restaurant has its DNA already—this summer it will be 9 years old. I hope this restaurant can live on for a long time. But I do sometimes dream of opening a restaurant that is all white. I dream of other design challenges, other things that are remarkably different from our space now.

If it’s summer, the flowers and herbs that you see in the garden will also be on your plate. If it’s winter, you see that nothing is growing outside, and the menu reflects a starker style.

MJL: It’s summertime in New York right now. Are there particular things growing in the Northeast that you’re particularly excited about that will make their way into the Aska dining room?

FB: I’m always excited about the berry season—I love berries. But New York’s climate is so different from the one back home in Sweden. Over there, we have a gradual warming period: temperatures slowly rise, plants steadily bloom, and nature peaks in the summertime.

Here in Brooklyn, winter is long and cold, and spring barely exists. It arrives all at once, and suddenly it’s the second week of June and—boom—it’s summertime. Back in May, we had ramp season for about two weeks, and then it jumped to 75-degree days and berries—it’s a short transition.

That makes our winter menu very drawn out. We don’t have access to that many spring vegetables in New York until closer to summer. Then we have a long, warm autumn. You can eat strawberries here in December, I’m not kidding (laughs).Then it gets ice cold again.

Right now, I love watching nature go through the pale green leaf transition and then seeing the flowering meadows that arrive in the summertime. Of course, if you pay attention, you end up loving every single season. Spring is always so refreshing—it becomes the driving force that sets the pace for the year ahead. Summer is magical, and fall is so rich and exceptional. You harness that energy to bring you through the winter until the cycle begins again.

MJL: Has anything surprised you about the climate of the Northeast? Are there things that remind you of Sweden?

FB: Yes, but each year here is so different. New York has good years and bad years, rainy years and dry years, hot years and milder years. That affects the food. For as long as I can remember, no two years here have been the same. Sometimes it feels like back home, but it varies greatly. Some years, I can go pick ramps in my ramp spots, and you can spot them easily because they’re the first things to pop up. Other years, you can’t find them because they’re hidden by grass that’s already a foot tall. That’s what fascinates me. It’s different every year.

That’s what I love about going out in nature. It’s like Christmas morning every time.

ASKA

47 S 5th St

Brooklyn, NY 11249